- Home

- Projects & Programs

- Olive B. McLin Community History

- Original Olive B. McLin Community History Project

- Resources

- For Educators

- Scholars / Research

- The Library

- Black history comes to life online

- Bus to Destiny

- Trunk of Hope

- Meet The Graysons

- St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream

- To Be Black and to Live in St. Pete

- People of St. Pete

- Chris Read – Local Writer

- Earl Spinks – Chef & Humanitarian

- Jalessa Blacksheer – Activist & Community Leader

- James B. Sanderlin – Judge

- Thank you Students & Volunteers!

- Partners

The Buried History of Methodist Town and the Gas Plant District

Two forgotten neighborhoods sit north and south of Central Avenue in St. Petersburg, Florida, Rich in history and vibrant in culture, Methodist Town and the Gas Plant district remained a staple in the African-American community of St. Petersburg for more than half a century, until the bulldozers came, first to build the highway system and then to clear space for a baseball stadium in a city without a team.

Below, NNB reporters and community members try to recover part of the lost history of these two predominantly African-American neighborhoods.

Segment One: Donaldson, Pepper Town, Cooper’s Quarters and Methodist Town

John Donaldson and Anna Germain, who later became his wife, moved in 1868 to settle permanently in the frontier community that later became St. Petersburg. The Donaldsons earned wide community respect as they had successfully established themselves as capable entrepreneurs. “Peck & Wilson, 2008, p. 13”

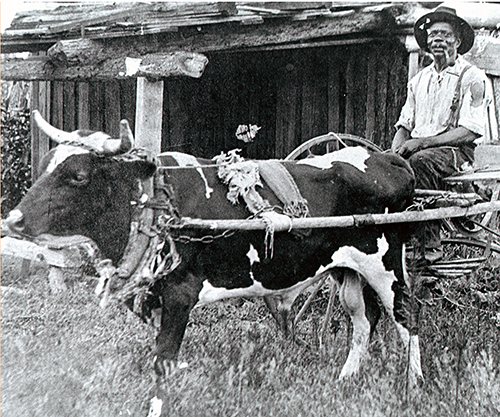

John Donaldson Oxcart 1885 – Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History: P00968

John Donaldson, pictured here, and his wife Anna were the first African Americans to settle in the area that would later be deemed Pinellas County. Donaldson, a former slave, moved to St. Petersburg in 1868 and became a successful farmer, owning 40 acres of land one mile NW of Lake Maggiore. He and his wife are currently buried in Glen Oaks Cemetery.

Moving forward, from 1888 to 1889 the men of the Orange Belt Railway tracks had been the first African Americans that worked and lived together, and slept alongside the rail bed in makeshift shelters or on the ground. However, most workers that assisted with building the Orange Belt had stayed or decided to move and settle in an area called Pepper Town, which is east of what also became known as Ninth Street North, along with what also became Third and Fourth Avenues. “Peck & Wilson, 2008, “p.14)

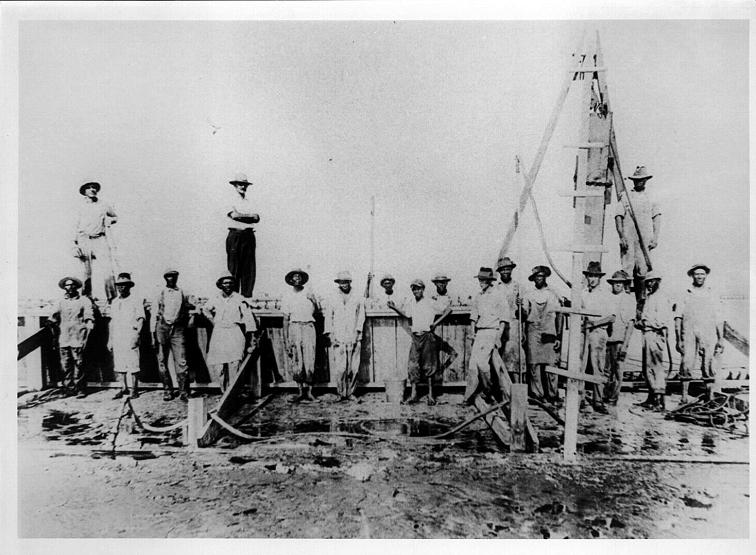

Laborers seawall 1913.

African American laborers building the seawall in 1913.

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History – P01345

John Donaldson, circa 1900. Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History: P01649.

Pepper Town had flourished into the 1950s, and remains had survived into the 1960s. This neighborhood’s name had derived from James King (first African American police officer and resident) relating this name to how most residents in Pepper town grew peppers of all kinds in their gardens, yards, pots and tubs. “Peck & Wilson, 2008,” p.14)

Through the 1890’s into the early 1900’s, Ninth Street South became populated by another African American community, south of First Avenue South, known as Cooper’s Quarters. This was also the beginning of what eventually became known as the Gas Plant area.

Historic Bethel A.M.E. Church, established in 1894 on 912 Third Avenue North. Methodist Town was named after Bethel A.M.E., one of the first churches for the local African-American population in the St. Petersburg area. Photo: Courtesy of Gwendolyn Reese and The Weekly Challenger.

During 1910 St. Petersburg’s population was a total of 4,127 residents, comprising 1,098 African Americans (about 27 percent), according to the federal census, as time went on that number continued to grow.

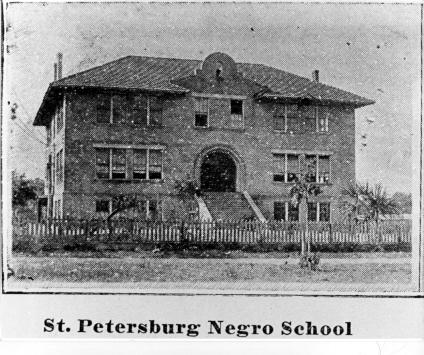

Davis Elementary (which was known as Davis Academy prior) opened on 944 Third Avenue South and was the first formal school for African-American students.

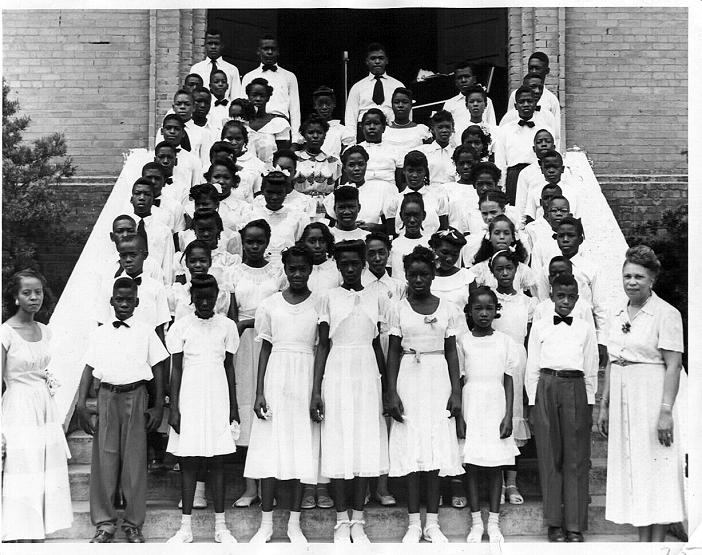

Davis Academy 1920

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History: P01460.

Davis Elementary 1922

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History: P0.4101

Caption: African American children playing basketball at Davis Academy

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History

Caption: Children in costumes Davis Academy 1927

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History

The Democratic Party conducted a “whites only” primary in a city election in 1913. Another “unofficial” one would be held in 1921, and a 1930s city charter had provision for a white primary.

In 1914 townspeople and nightriders from the countryside lynched John Evans at Ninth Street South and Second Avenue. They suspected him of murdering white photographer Ed Sherman.

Ed Sherman’s lawyer told his hometown Camden, New Jersey, newspaper that city leaders met in secret to plan the lynching.

Caption: John Evans’ lynching 1914.

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History

The population of St. Petersburg in 1920 had grown to 14,237, including 2,444 African Americans (about 17 percent), according to the federal census.

Adding weight to segregation policies, St. Petersburg police would arrest any white men that would be in the black areas at night, despite their age or social standing.

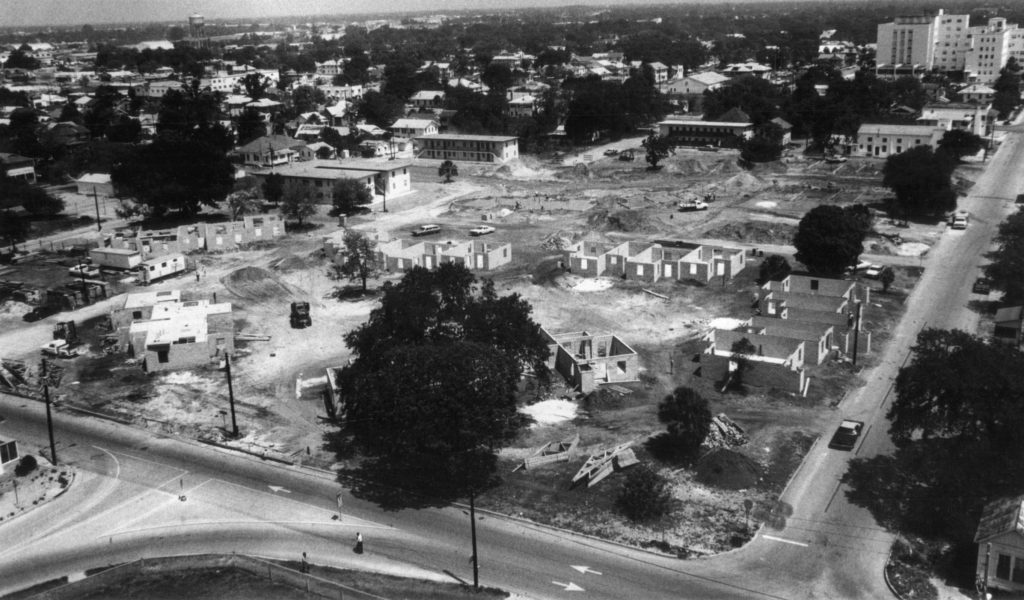

Caption: Aerial Photo of Methodist Town and Gas Plant area in St. Petersburg in 1926.

Photo courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History

Gas Plant District

The Gas Plant neighborhood, circa 1970, where the redevelopment caused 285 buildings to be bulldozed; more than 500 households, 9 churches, and more than 30 businesses moved or closed.

The Gas Plant District was the name of the area that is now occupied by Tropicana Field.

Methodist Town was a predominately African American neighborhood.

Copyright 2016 nicdark.com