- Home

- Projects & Programs

- Olive B. McLin Community History

- Original Olive B. McLin Community History Project

- Resources

- For Educators

- Scholars / Research

- The Library

- Black history comes to life online

- Bus to Destiny

- Trunk of Hope

- Meet The Graysons

- St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream

- To Be Black and to Live in St. Pete

- People of St. Pete

- Chris Read – Local Writer

- Earl Spinks – Chef & Humanitarian

- Jalessa Blacksheer – Activist & Community Leader

- James B. Sanderlin – Judge

- Thank you Students & Volunteers!

- Partners

African-American Hertiage Trail

The African-American Heritage walking trail celebrates the rich cultural history of St. Petersburg’s African-American community.

The neighborhood that surrounds the intersection of 22nd Street S. and 9th Avenue S. was once the most important area, in the most vibrant African American neighborhood, during St. Petersburg’s segregation era. By law, African Americans were forced to live in this area. Despite this violation of freedom, the community created a self sufficient and independent spirit. African Americans generally were not welcome downtown or in white residential areas. This remained the case until the mid-20th century, when integration began to offer new opportunities. Once considered out in the country, relative to downtown St. Petersburg, the community began to develop among palmettos and pine woods during the 1920s. People began moving into the area because new industries offered jobs ad because white city leaders encouraged the movement of African Americans away from the older black neighborhoods.

The core of 22nd Street S. lay between 5th and 15th Avenues S., where stores opened offering furniture, clothing, groceries and sundry items. Restaurants sprung up along the street and every professional service was available. It was also an entertainment hot spot with nightclubs and beer gardens. The king of them all was the Manhattan Casino, which held dances featuring house bands and frequently played host to America’s finest musicians and gospel singers. A few Jewish merchants, also banned from opening in St. Petersburg’s downtown, got their start on 22nd Street S. In contrast to the commercial corridor, the 9th Avenue S. corridor between 16th and 24th Streets S. became an avenue filled with churches, schools and civic organizations. On opposing ends were Jordan Elementary to the west and Sixteenth Street Junior High and Immaculate Conception Catholic School to the east. For decades, a dozen churches along the avenue, or near it, opened their doors to the faithful of many denominations.

Gradual integration and the coming of the Interstate damaged the street’s commercial, professional, and entertainment bases while damaging its cultural identity. Serious decline was evident by the 1970s. More specific information is available on markers situated along both the 22nd Street S. and the 9th Avenue S. corridors. We hope you will walk them. You will learn about entrepreneurs, civil rights, pioneers, caring people, and personalities who cast giant shadows in the community. Most importantly, you will you will come to appreciate the resilience of people whose ingenuity, talent and perseverance let them thrive amid the era’s restrictive social system.

The above image was part of every trail marker.

The above image was part of every trail marker.

The trail has two corridors, both beginning at the Carter G. Woodson African American Museum. Both paths share the same starting trail markers: The Beginning and End of an Era

9th Avenue S. Marker 1: The Beginning

Dirt Trails to Main Street

During the 1920’s, on the edge of a growing city barely 30 years on the map, African Americans began to create their own community along a dirt trail known as 22nd Street S. It was far in the country, part of a sprawling tract that the city government recently had annexed. It was a place of palmetto and pine, not far from a low-lying spot called Moccasin Bottom, where woodsmen wearing protective “snake boots” made their axes ring and their saws sing while harvesting lumber or clearing land. Eventually, 22nd Street S. grew into one of the nation’s African-American main streets, a miniature version of Beale in Memphis, of Sweet Auburn in Atlanta, or of Ashley in Jacksonville.

Jim Crow Laws and Custom

Weel about and turn about and do jis so, Eb’ry time I well about I jump Jim Crow. – from “Jump Jim Crow” by T.D. Rice.

Jim Crow was a series of racial segregation laws enacted after the Civil War. Originating with a caricature of blacks performed by T.D. Rice in 1832, the term “Jim Crow” soon became a negative term. When new segregation laws were passed, they became down as “Jim Crow Laws.” More than a series of laws, it was a way of life in which blacks were relegated to the status of second-class-citizens. They could not shop, find entertainment, receive professional services, or even attend most churches. The exclusion fostered need and energized the rise of streets such as 22nd Street S. which became a commercial, professional, and entertainment thoroughfare for black St. Petersburg.

John Donaldson

John Donaldson and his wife, Anna Germain, were the first African-American settlers on the Pinellas peninsula when they arrived in 1868 as employees of Louis Bell, Jr. The well-respected couple purchased 40 acres in 1871 on present-day 18th Avenue S. and established a truck farm with cattle, hogs, and an orange grove. In 1887, Donaldson signed a petition calling for a separation from Hillsborough County. He died in 1901, ten years before the separation occurred.

Elder Jordan, Sr.

Born a slave around 1850, Jordan and his family came to St. Petersburg in 1901 when the city was beginning to win a reputation as a resort. Jordan is said to have originally been from Fort White, Florida, in Columbia County. Records also show Jordan marrying Mary Frances Strobles, a Cherokee woman, in 1885 in Rosewood, Florida, site of the infamous massacre of African Americans four decades alter.

A tall man given to wearing black suits and cowboy boots, Jordan quickly established himself as an entrepreneur in St. Petersburg, selling produce and opening a livery stable. He made deliveries in a horse-drawn wagon and turned the front room of his house on 9th Street S. into a produce stand. Later, he began buying tax deeds and started accumulating property, becoming a pioneer developer. He built some of the very early housing in the neighborhood and established early “courts,” a traditional, African-American residential development style. He was a trustee for the early African-American schools. Both Jordan Elementary and the Jordan Park Housing Complex in front of you were named in his honor. According the enduring community lore, Jordan was wealthy enough to loan money to the city government during hard times after the stock market crash of 1929. He and his son built the iconic Manhattan Casino.

Elder Jordan, Sr. died in 19036 before the street he helped energize hit its stride. It picked up momentum after World War II and peaked in the early 1960s.

9th Avenue S. Marker 1: End of an Era

As the heart and soul of St. Petersburg’s African-American community during the segregation era, 22nd Street S. became the nerve center of the city’s civil rights movement.

Segregation and Recreation

During this era, even such simple activities as swimming carried restrictions for African Americans. Virtually all public beaches were off limits. The exception was a spit of land at the end of Atlantic Coast Line railroad tracks that ran along 1st Avenue S. It was called the South Mole, and it was as much an industrial storage area as it was a recreational beach. Blacks had no public swimming pools until 1954, when the Jennie Hall Pool, named for the white woman who donated $25,000 for its construction, opened in Wildwood heights.

Sanitation Strike

The 1968 sanitation strike was led by cigar-chomping, hymn-singing Joe Savage. Starting from the Jordan Park Community Center (now the Carter G. Woodson Museum), striking workers marched on City Hall more than 40 times during the 116-day walkout. Helmeted officers confronted the marchers. City officials fired the workers, and the police arrested Savage. A. D. King, the brother of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., joined the marchers. So did former Southern Christian Leadership Conference president Ralph Abernathy. Four days of violence shook the neighborhood as the strike stretched into August. When the walkout ended, the workers had won a small raise. The strike had an impact beyond material results. It was later recognized as a seminal event in St. Petersburg’s civil rights movement, largely because it called attention to inequalities. It also energized the community and encouraged further activism for equal rights. Among the sanitation strike marchers was a young attorney, James B. Sanderlin, who marched numerous times with the sanitation workers. Said Joe Savage of Sanderlin: “He was an educated man who was working for uneducated men. He was up high, but he jumped down low right with us uneducated mean. He stuck right in there with us. He brought us through, and I thank God for that.”

Attorneys for the Cause

Fred G. Minnis, Sr., one of St. Petersburg’s first black lawyers, was sometimes referred to as “the father of law” in the black community. Minnis also earned a reputation for recruiting and helping young people to go to college. He reportedly assisted more than 500 students who enrolled at Howard University and other predominantly black schools. He formed a partnership with attorney Isaiah W. Williams and opened an office on 22nd Street S.

In 1962, Fred Mnnis persuaded James Sanderlin to come to St. Petersburg to practice civil rights law. For the next three decades, Sanderlin took and won cases that established him as a civil rights hero throughout the Tampa Bay area. In 1966, he represented 12 black police officers in a suit against their employer, the City of St. Petersburg. Known as the “Courageous 12,” the officers asked for the right to patrol white neighborhoods and to be able to arrest white people. The suit was won on appeal. Sanderlin’s biggest victory was a suit against the Pinellas County school district that formally ended public school segregation in 1971 through court-ordered busing. Sanderlin eventually became Pinellas County’s first black county and circuit judge and later was appointed to the Second District Court of Appeals.

Other members of the firm, Frank White and Frank Peterman, also paved the way for equality in the law. White, who started his career as an unsalaried volunteer in the public defender’s officer, eventually was elected a circuit judge. Frank W. Peterman was the first black person to win a Pinellas primary election for the state legislature in 1968.

9th Avenue S. Marker 2: Jordan Park Housing

The Great Depression brought a decline in tourism and construction. Local leaders tried to revive tourism and provide visitors with “a sanitized social environment” by downplaying the size of the local black community. In spite of fewer jobs, the black population grew 61% during the 1930s with overcrowding and substandard housing conditions rampant. In an effort to provide improved housing and to remove African American from the neighborhoods closer to downtown, the Jordan Park Housing Complex was built.

Funded by the U.S. Housing Authority and named after Elder Jordan, Sr., the two phases of construction incorporated 446 apartments. The project was a success with full occupancy. It provided improved housing to hundreds, but the all-black complex also reinforced segregation and the “separate but equal” construction of facilities.

A Population Divided

Both phases of the project were the target of opposition from the landlords of substandard housing in the black neighborhoods. Among other fabrications designed to protect their own property investments, opponents stated that public housing would destroy African-American initiative. Opposition during phase two was so intense that City Council dodged taking a vote leading to a city-wide protest against the opponents. This resulted in a vote which put the issue up for referendum. The election revealed that voters favored proceeding with phase two of the Jordan Park Housing Complex with a vote of 2,731 to 2,080.

The Golden Era

After construction, Jordan Park became a prestigious address with a long waiting list of people wanting to move into the complex. Instead of destroying initiative, as opponents claimed would happen, the opposite occurred. When families topped the income-level requirements to be Jordan Park residents, they often purchased or built their own homes. A 1955 report stated that 18 of 32 houses built in the nearby Carver Park Subdivision had been built by Jordan Park “graduates” and that 181 former Jordan Park residents owned their own homes.

Marie Yopp, Jordan Park Resident

Among Jordan Park’s early residents was Marie Yopp. Although trained with more than eight years of experience as a nurse, Yopp had difficulty finding work and initially served as a maid with a local doctor. Deciding to continue her education, she attended Florida A & M University and completed her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing in 1943.

Yopp joined the Mercy Hospital staff as a registered nurse in 1946. While there, she founded the Registered Nurses (RN) Club. Yopp became the first registered black nurse at the Pinellas County Health Clinic located next to Mercy Hospital. She later received a Master’s degree from Columbia University, and served as a public health nurse at Sixteenth Street Junior High. Yopp resided at Jordan Park until acquiring her own house in the mid-1950s.

9th Avenue S. Marker 3: Pioneer Schools

Gibbs High School

Opened in 1927, Gibbs High School, originally intended to be a white elementary school, was the first public secondary school for African Americans. It was located a half-mile west of here on a four-acre parcel near 9th Avenue and 34th Street S. According to Ernest Ponder, former student and teacher, school officials felt that there wouldn’t be any problems with providing a black high school because it was in an isolated area. The school initially had only eight classrooms, none with electricity.

Under the leadership of George W. Perkins, who served as principal from 1929 to 1932 and again from 1938 to 1946, school facilities improved. Perkins, his faculty, students, and volunteers raised money and built a “gymnatorium” under the supervision of African-American contractor P. P. Perkins. During the 1930s, teachers pledge their salaries to help purchase a dilapidated bus nicknamed the “Blue Goose,” which students paid a nickel to ride to keep it running.

In 1950, it was one of the first black high schools in the southeast to be accepted as a member of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Teachers such as Olive B. McLin, Ernest Ponder, Ruby Wysinger, Eloise Perkins, Lena Lester Brown, Lou Brown Sr., N.L. “Love” Brown, Freddie Dyles, and Emanuel Stuart, among other, served as role models and mentors to generations of students.

Jordan Academy

Jordan Academy, later known as Jordan Elementary, was built in 1925 and named after Elder Jordan, Sr., who served as a trustee for African-American schools. Jordan Academy functioned as the neighborhood elementary school for the growing 22nd Street corridor, while Davis Academy continued to support the neighborhoods around Methodist Town and the Gas Plant.

When completed and opened on September 1, 1925, the school had six classrooms on each floor with a central entry hall and 21 teachers under the administration of Principal George W. Perkins. Operating on a double schedule, Perkins oversaw the student body of Jordan Academy, which had 1,100 children by 1927. He also fought to extend the school term from six months for “Negro” children to the nine month term typical for white children. Jordan Elementary served as an anchor and cultural center for the 22nd Street S. community and instilled the value of education to thousands of children for 50 years.

Davis Academy

In 1914, Davis Academy, a school for African-American children, opened at 950 3rd Avenue S. It was named for Ned Davis, who helped establish the first African-American school in a three-room, wood-frame building nearby on 2nd Avenue S. in the city ca. 1910. Education in “Negro” schools originally focused on manual training and domestic science rather than academic studies.

Students prepared and served meals and performed as a chorus in Williams Park in order to raise money to help extend the school term.

9th Avenue S. Marker 4: Civic Associations

Denied access to whites-only organizations, African-American men formed their own clubs early in St. Petersburg’s history. In addition to the well-known fraternal societies, clubs organized by occupation, churches, and recreational interests enriched men’s lives. Many activities were sponsored by churches with the Ushers Circle and Ministerial Alliance the leading religious clubs catering to men. There was a Downtown Workers Association for hotel employees, railroad porters, cafeteria workers and other African-American men working in or near the downtown business district. The Negro Barber’s Association actively supported their members. The Sportsman’s Club and YMCA sponsored community dances and other recreational activities. College fraternal organizations were a source of fellowship, community leadership, and advocacy.

Modern Free & Accepted Negro Masons of the World

The first recorded local organization is the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge 109, which formed in 1893. Although founded in another neighborhood, it is worth noting because the lodge is the oldest Masonic organization in St. Petersburg. It predated the city’s first white Masonic lodge, and was formed by early black settlers. The 22nd Street S. neighborhood Masonic Lodge was located at 1210 Union Street S. and was constructed in 1949.

International Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks

Another of the oldest local organizations, the brotherhood of Negro Elks hosted the 1942 4-day annual convention. It included a parade down 22nd Street S. and a grand ball at the Manhattan Casino. In the picture to the right, W. T. Stockton, William Lattimore, E.H. McLin, and Samuel Joseph form the Elks Memorial Committee in 1969.

The Ambassador Club

One of the most influential, the Ambassador Club counted its members among the city’s most prominent African-American men. Dr. Ralph Wimbish is credited with founding the club in 1953. The club was formed by black professionals, educators, and businessmen including Dr. Orion Ayer Sr., Dr. Robert J. Swain, Dr. Fred Alsup, Samuel Blossom, Sidney Campbell, George Grogan, John Hopkins, Ernest Ponder, John Rembert, and Emanuel Stewart.

Among the Ambassador’s many services to the community was advocating and gaining acceptance for the first African-American float in the city’s annual Festival of States Parade in 1954. In addition to advocating for civil rights, the Club established the Milk Fund which provided milk for underprivileged children at Jordan, Perkins, Wildwood, Davis, and Sixteenth Street elementary schools as well as Happy Workers, Community Day, Methodist Town, and Sixteenth Street nurseries. The club also organized numerous fundraisers to benefit the community.

Veterans Organizations

Although the names of these servicemen have been lost to history, they represent the many men and women who courageously served in the armed forces during periods of conflict. During World War II alone, nearly two thousand black men and women from St. Petersburg served their county. After their return, local veterans formed organizations including the Sons of Colored Veterans, Colored Veterans of the World War, Pinellas County Negro Veterans Association, and Amvets, among others.

NAACP

In 1933, as the Great Depression settled in and local African Americans were limited to certain areas, the St. Petersburg Branch of the NAACP formed. The NAACP organized stand-ins at theaters, boycotts of businesses, and sit-ins at lunch counters which refused to serve black patrons. Local branch leaders have included F.A. Dunn, Morris Milton, and Dr. Ralph Wimbish, who occupies a front seat at the organization’s meeting in the photo to the right.

9th Avenue S. Marker 5: Women United

City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs

Denied access to white civic groups under segregation, local African-American women sought to establish their own organizations. In 1938, Fannye Ayer Ponder, teacher and wife of local physician Dr. James M. Ponder, founded the City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs along with notable women such as Mary L. McRae and Olive B McLin. The local organization quickly forged an affiliation with the Florida and the National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.

The purpose of the City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, as outlined in its construction, was “to unite the efforts of all the colored women’s clubs in St. Petersburg in order to promote better educational advantages, to promote social and civic improvements, establish recreation for young people, and to educate the citizenry towards better and higher standards of living.” It served as an umbrella organization under which seven individual clubs affiliated. Eventually, more than 12 clubs joined the City Federation. By 1953, membership in the clubs from the Federation totaled more than 350 women.

Member Clubs

Non Pareil Club (1927)

Margaret Washington (1929)

Quest (1934)

Socialites Club (1938)

Piquant Los Jovens (1938)

Phyllis Wheatley Forget-Me-Nots (pre-1942)

Non Pareil Charmerettes (pre-1942)

Sojourner Truth (pre-1942)

Mary McLeod Bethune’s Victorettes (1943)

Merrymakers Club (pre-1955)

Les Juene (pre-1955)

Hearts of Clanzell (1962)

John F. Kennedy Club (1962)

Melrose Clubhouse

City Federation members initiated a campaign to acquire land and construct a clubhouse. Even non-Federation clubs donated toward the construction of the building, such as the Beauticians’ Club which donated $5 to the project. White churches also supported the effort. The First Congregational Church pledged $1,000, and sponsored a play, “Wings Over Jordan,” in 1941 as a cooperative fundraiser. Church member, Dr. Charles A. Lauffer, donated three acres of land and $5,000 toward construction “upon the condition and restriction that they said property shall be improved and used for educational, social, recreational facilities for colored people, especially a playground for colored YMCA, YWCA, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of St. Petersburg, Florida, and for gardening by and for the needy colored people of said City.”

Opened in April 1942, the Melrose Clubhouse, (1801 Melrose Avenue S.), served as a focal point of community service and charity work. During World War II, the clubhouse, along with Jordan Elementary, acted as a war nursery for African-American children. In1945, the local YMCA leased space from the Federation and established the Melrose Park YMCA for African-American men and boys who were not allowed to use the main facility downtown. In 1959, the City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs sold a portion of their property to the Pinellas County School Board for the construction of Melrose Elementary.

Laurffer Branch YWCA

The YWCA offered programs for African-American girls through the schools long before opening their first office in the Gas Plant neighborhood in 1948. Dr. Charles Lauffer, who had generously donated to the construction of the Melrose Clubhouse, passed away in 1946 and bequested a yearly income to the YWCA which named a new branch in his honor. In 1950, a building was donated and moved to 2129 15th Ave S. to serve as the Lauffer Branch YWCA, which remained open into the 1970s. From January through June 1950, the Lauffer branch served 2,701 girls and women up to age 35.

9th Avenue S. Marker 6: Avenue of Faith

This neighborhood is partly defined by the many churches situated along 9th Avenue S. These churches have been housed in imposing buildings, modest structures, and tiny storefronts. Although many date back decades, all have enriched the community’s life through spiritual and social outreach.

All seven major black denominations have played a role in the moral and social development of the neighborhood. In 1939, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) prepared a Historical Records Survey of churches throughout Florida. At that time, approximately 19 of the 123 churches in St. Petersburg operated in this neighborhood. By 1951, 24 of the 139 churches in the city operated here. Some of the original buildings remain, while other have been lost, many due to the construction of I-275. Among others, you can see the following churches in the neighborhood:

Queen Street Church of God in Christ

1732 9th Avenue 2.

Initially called the “13th Avenue Store-front Mission,” the Queen Street Church of God in Christ was organized in 1945 in a storefront on 13th Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets. The congregation built this building as their current sanctuary in 1946.

20th Street Church of Christ

820 20th Street S.

Starting with tent meetings in 1927, the organization of the 20th Street Church of Christ was a cooperative effort between a black evangelist, Brother Marshall M. Keeble, and two white men, Brothers Richardson and M. A. Dye, who worshiped at the Church of Christ in Ninth Street N. The church grew rapidly with one tent meeting in 1929 adding 92 to the congregation. By 1932, the church constructed a small white building at 820 20th Street, which had a baptismal pool described as “very cold and scary looking.” Although there is a new main sanctuary for this congregation, their original building is still part of the church complex.

Greater Mount Zion African Methodisst Episcopal Church

919-21 20th Street S.

The first meeting of the Greater Mount Zion AME Church took place at Just-Rite Cleaners, where the church’s first pastor, Reverent F.L. Gillians, was employed. Fulfilling an immediate goal of purchasing land, the first services were held in a new wood frame building in 1925 at 919-21 20th Street S. The original building was demolished after this sanctuary was built in 1948. This congregation has since moved.

Stewart Memorial CME Church

2137 9th Avenue S.

Organized in 1911, Stewart’s Memorial CME Church erected its first sanctuary prior to 1913 in an area known as Pepper Town. Named after Bishop G.W. Stewart, the congregation re-elected the sanctuary at 2137 9th Avenue S. in 1929. In 1937, Miss Elise Friedgen, a white winter resident and member of Pasadena Community Church, donated a new education building in memory of her late brother, Charles Friedgen. Constructed adjacent to the sanctuary, the building provided Sunday school classrooms and an assembly room. The congregation continued to use this facility until 1985, when they relocated.

Mount Zion Primitive Baptist Church

2051 9th Avenue S

Marked by two stone lions in front, the Mount Zion Primitive Baptist Church building is now occupied by the Abundant Life Ministry congregation. Established in 1927, the Mount Zion Primitive Baptist Church congregation initially met in a commercial building above a store on 22nd Street between 9th and 10th Avenues S. Services moved to a small remodeled house on 26th Street until the church was built around 1930.

Elim Seventh Day Adventist Church

2101 9th Avenue S.

Originally organized in 1915 in Pepper Town, the Elim Seventh Day Adventist congregation met at several locations before purchasing the lot at the corner of 9th Avenue S. and 21st Street S. In 1925 and constructing a wood frame church building in 1927. As the congregation expanded, the building was renovated several times before the congregation moved to a new location in 1976. The New Congregation Church of God now owns this building.

Mount Zion Progressive Missionary Baptist

948 20th Street S.

In 1928, some members of the First Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church decided to form a new congregation and organized the Mount Zion Progressive Missionary Baptist Church. A small, wood-frame building on 20th Street S. served as the original sanctuary. With a growing congregation, the church built a new sanctuary in 1946 at 948 20th Street S, which now serves as the church’s Children’s Center. The current sanctuary is located at 955 20th Street S.

9th Avenue S. Marker 7: Happy Workers-Trinity Presbyterian

Happy Workers Day Nursery and Kindergarten

Founded in conjunction with Trinity Presbyterian Church by its pastor, Reverend Oscar Monroe “O.M.” McAdams, and his wife, Willie Lee, Happy Workers Day Nursery opened in 1929 with five children whose parents paid 25 cents a week for their care. Mrs. McAdams, who was the driving force behind the nursery, based the facility on the founding principle of child development in an environment of love, trust and respect. The daycare started n a small church owned building. In 1943, the nursery started offering infant care at a cost 2 dollars per week. In 1945, the school built a new building, expanding to accommodate 200 preschoolers each year. Happy Workers, a major cornerstone in the early education of thousands of children in St. Petersburg, remains a place where children learn to be peacemakers, where they are loved, and most of all where they are educated not only in the social graces, but also academically.

Rev. Oscar Monroe McAdams

(1887-1976)

Rev O.M. McAdams, a scholar fluent in five languages, taught mathematics at Gibbs High School and Sixteenth Street Junior High for approximately 28 years. Born and raised in South Carolina, he graduated from Johnson C Smith University in 1915 and from Auburn Theological Seminary in Auburn, NY in 1918. At his first pastorate in Greenville, South Carolina, he met and married Willie Lee, who was a member of his staff. In St. Petersburg, he pastored Trinity Presbyterian Church form 1929 to 1965. He also served as president of St. Petersburg’s Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance and as president of the St Petersburg branch of the NAACP for five years.

Trinity Presbyterian Church

Founded in 1928, Trinity Presbyterian Church thrived after Rev. O.M. and Willie Lee McAdams came to St. Petersburg in 1929. After meeting for a year at Jordan Elementary, the congregation remodeled a residence at the corner of 19th Street and 9th Avenue S. into a church and moved the daycare into another building on the property. Under the Mcadamses, the church established the first Vacation Bible School in the area, which grew so popular that the 500 students had to be accommodated at Jordan Elementary. In 1947, the congregation sold their church building to the St. Petersburg Metropolitan Council of Negro Women, who moved the building across 9th Avenue to Serve as their clubhouse. The congregation, with the assistance of architect Henry Kohler and African American contractor Peter P Perkins, dedicated their new facility on August 1, 1948. After Mrs. McAdams passed away in 1956, rev. McAdams continued to pastor the church until 1965. The church shared the property with Happy Workers until 1967, when the congregation moved to 22nd Avenue S.

Willie Lee McAdams

(1895-1956)

When she witnessed young African American children playing unsupervised in the street while her parents worked, Willie Lee McAdams and her husband decided to open Happy Workers Day Nursery and Kindergarten in 1929. She earned a teaching degree from Haines Normal Institute of Augusta, GA in 1924, and received a diploma from the Board of Christian Education of the Presbyterian Church USA. As the wife of Presbyterian minister, Reverend O.M, she used her contacts with other churches and the white community to raise funds, but property and open the day care. The facility she started continues to provide a safe, education environment for children while meeting the standards from day care facilities.

9th Avenue S. Marker 8: Early Housing

Although the first plats in the neighborhood were filed in the early 1900s, a settlement was sporadic until the mid 1920s. Early housing in this area was decidedly vernacular, meaning folk building without the benefit of formal plans. While most housing consisted of one story, wood frame buildings with little to no added features, house types varied. These houses were typically found in rural areas, as this area once was. Many of the types shown here, such as the shotgun and the single and double pen, are types that derived from the west coast of Africa. They utilized a form that fostered togetherness, cultural traditions, and community values that laid the foundation upon which this new architecture was designed. The front porch is also a distinctly African derived architectural feature, not being found in Western European architecture prior to this time. The front porch provided a cool space to gather on a hot evening and was quickly adapted and reused in the US. These principles and design techniques were then assembled using European Colonial framing techniques. The photos you see here were taken from a “Sub standard Housing Survey” conducted in late 1938. The houses were then rechecked for improvements in 1940 and 1941. Most of these house forms no longer exist in the city. After WWII, many servicemen, including African Americans, returned to St. Petersburg and built new homes using the GI bill. These new Minimal Traditional and Ranch style homes filled vacant lots in the 22nd Street S neighborhood, many of which remain today.

Marker 9 has two parts.

9th Avenue S. Marker 9, Part 1: Campbell Park

Thomas C. Campbell

In 1918, Thomas C. Campbell relocated to St Petersburg from Knoxville, PA. In addition to running the Campbell Hotel at 219 3rd Ave N, Campbell bought land between 12th and 16th Streets S, bounded by 5th and 9th Aves S, which became known as the Campbell Subdivision. Largely divided into lots and sold to African Americans, a portion was set aside specifically for use as a park for the African American community

Campbell Park

Campbell Park, located just across 16th Street S from John Hopkins Middle School, was once the scene of all major African American sporting events, community celebrations, and parades. In addition to being the home of the Dreamland Dance Hall, the park hosted homecoming parades, Glee Club concerts, mini-golf tournaments, shuffleboard and every Gibbs High School football game between 1930 and 1966. At that time, Campbell Park was nothing more than a sandlot with a fence around it. During dry spells, officials often had to stop games in order to let the dust clear, thereby earning the appropriate but unfaltering title, “Dust Bowl.”

During the segregation era and despite adverse conditions, Negro baseball teams played regularly on the field. The players’ dugout behind first base was used nearly every day. In 19928, the Sunshine Babies started a winning streak that carried them through the Southeast for 16 straight victories. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Pelicans of the Florida State Negro Baseball League won the League championship and finished 2nd, 3rd and 4th. The poor conditions of the field did not keep these top notch players from success. Eugene H McLin, the City’s first “Negro” Recreational Director, was hired in 1945. He played an important role in the improvements to the baseball field that occurred in 1952.

St. Petersburg Negro League Teams

- Florida Gators

- Florida Stars

- St Petersburg Blue Stars (women)

- Sunshine Babies

- Florida Monarchs

- Peters Palace Stars (later knows as Pelicans)

- Black Saints

- Blue Jays

- Grays

Owners

- Elder Jordan

- James Smith

- R. C. Calhoun

- Jim Barrett

- Henry Brockington

- Buster Johnson

- Sam Woods

- Bill Pettigrew

- Jack Peters

- Charlie Williams

- George Grogan

- Robert Smith

- Author Graham

- Joe Bryant

9th Avenue S. Marker 9, Part 2: From farmhouse to to schoolhouse

Immaculate Conception Catholic School

Catholic instruction began around 1940 when Sister Evangeline Marie of St. Anthony’s conducted a catechism class for 39 colored children. Rt. Rev. Joseph P. Hurley, Archbishop of the St. Augustine Diocese, saw the need for a church and purchased Gills Dairy in 1946. This tract of land is located near where you are standing at 9th Ave S and 16th Street S adjacent to the Sixteenth Street School. The land housed an old farmhouse, a “cow barn,” and a few other small buildings, including a one story frame shed built in 1926.

Sisters Irenus and Jeanette conducted religious classes. In the first year, they were responsible for 20 children, ranging in age from five to 15, who received instruction in the shed. The first year was challenging. There was a lack of consistent attendance and winter temperatures made the shed too cold for instruction. However, the sisters persevered, and in 1948, the first mass was celebrated in the Immaculate Conception Church.

In Jan 1953, a kindergarten was established with three students. An administration building was built along with a building containing four classrooms. The numbers continued to grow, and by 1956, there were 203 students enrolled with six grade levels and a large kindergarten. With the kindergarten and 1st grade classes being large enough to need their own rooms, the remaining five grades had to share two classrooms.

A 2nd wing was constructed in 1956 that included two new classrooms and an assembly room. Enrollment continued to increase and the school continued to be subsidized by the parish. During the 1970s, Immaculate Conception was combined with St. Joseph’s school.

Sixteenth Street School

In order to relieve overcrowding at Jordan Park and Davis Elementary Schools, the Sixteenth Street School opened, just beyond where you are standing. When the school was completed and dedicated on Sunday, Nov 2, 1952, it served students from kindergarten through 9th grades. Sixteenth Street School was a milestone of advancement for the black community in St. Petersburg, and everyone had a sense of ownership.

John H. Hopkins, Sr and Fred Burney served as co-principals. As leaders, both principals impressed upon the students a sense of appreciation and respect for the school. With the completion of Wildwood Elementary in 1956 and Campbell Park and Melrose Elementary Schools in 1962, the school was converted solely to a junior high school.

The Sixteenth Street Trojan Band directed by Sam Robinson had a reputation for excellence and was a showstopper whenever it performed. It was part of every parade and drew attention of black and white residents alike. “Trojan Band Again Steals Show” was a familiar headline n the St. Petersburg Times. In the 1960s, parents raised $1149 to buy band uniforms.

In 1955, a chapter of the National Junior Honor Society was formed with the induction of 30 students. The spirit of the school is captured in a poem by Ruth Steinberg reprinted from The Trojan.

“Real schools aren’t made by lads afraid to work hard to get ahead. When everyone works and nobody shrinks, you can raise a school from the dead. And if while you make your personal gain, your neighbor makes one too, your school will be what you want to see. It isn’t the school, it’s you.”

9th Avenue S. Marker 10: Empowered Negro Women

St. Petersburg Metropolitan Council of Negro Women

Fannye Ayer Ponder established the St. Petersburg Metropolitan Council of Negro Women in 1942. Mary McLeod Bethune, a family friend who had established Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach and mentored Ponder, had founded the National Council of Negro Women in 1935. This organization was intended to provide aid during the Great Depression and to encourage integration by developing competent and courageous leadership among African American women. Ponder acquired Trinity Presbyterian Church’s original building and moved it across the street to serve as their council house in 1947. Originally named the “council Retreat,” the house was intended to “aid in serving the growing needs of the adults and youth of the city to find wholesome recreational and social as well as educational outlets.” It was renamed the Fannye Ayer Ponder Council House in her honor.

Women’s Clubs and Organizations

African American women formed and joined a number of other social, professional, recreational, religious and civic organizations in the community. Women’s clubs also sought to provide programs of culture, education and entertainment to a population denied access to such activities in a segregated society. A few organizations accommodated men and women, but more commonly, the groups had separate affiliated clubs, such as the Royal Dukes and the Royal Duchesses. From the 1920s through the 1960s, many organizations contributed to the social fabric of the neighborhood.

Fannye Ayer Ponder (1904-1982)

Fannye Ayer Ponder moved to St. Petersburg in 1925 along with her husband, Dr. James Maxie Ponder and children, Maxie and Ernest. As a graduate of Florida A & M University, Ponder worked as a teacher at Gibbs High School, but played an even bigger role in her advocacy for women. Through her friendship and work with Mar McLeod Bethune, Ponder believed that civil organizations were a mighty vehicle for social improvement and change for people of color. Women especially could play a pivotal role in the improvement of their situation. In 1918, Ponder brought together seven women’s organizations, founded the City of Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and played a pivotal role in the construction of their Melrose Clubhouse. In 1942, Ponder established the St. Petersburg Metropolitan Council of Negro Women and acquired a clubhouse which the organization named in her honor. She was also instrumental in the creation of Gibbs Junior College.

Olive B. McLin (1907-1985)

Olive B. McLin came to St. Petersburg in 1918 when her father, Rev. R. D. McLin was appointed the minister at Bethel AME Church. With her mother, teacher and principal Regina McLin as inspiration. McLin taught English at Gibbs High School. She retired after 40 years, but remained active in the Metropolitan Council of Negro Women, Church Women United, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, and the Council on Human Relations.

22nd Street S. Marker 2: In the Name of “Progress”

Sno-Peak Drive In: The Place to Be, 2208 Fairfield Avenue S.

Opened in 1953, Leila Bowers was the long-time owner of this local ice cream shop beloved by children. With the assistance of Bower’s brother, cook Johnny Martin, the stand became known for much more. Local resident, Gwen Reese, recalled sweet memories:

“As a teen I recall the excitement of meeting up with friends in the parking lot for chicken gizzards with hot sauce, or a chicken sandwich with mayo… And what would either of them be without Sno-Peak to listen to musicians play their soul-stirring, hip-shaking music. And in the heat of the Civil Rights Movement, Sno-Peak was where we gathered to hear Stokely Carmichael talk to black and white, young and old, about our role in helping to change conditions in America.”

Johnson’s Realty, 800 22nd Street S.

After arriving in St. Petersburg in 1934, Cleveland Johnson, Sr. met white real estate agent Herman Meincke, who encouraged him to pursue training. Opening Johnson’s Realty in 1960, he became the first licensed African-American real estate broker in St. Petersburg. Frequently not accepting a commission from clients, he encouraged buyers to put it toward their down payment. A political activist, Johnson founded the Community Democratic Club and was active in the Pinellas County Democratic Executive Committee. Starting in 1967, his son, Cleveland Johnson, Jr., served as long time editor and owner of The Weekly Challenger, which provided a positive voice for the city’s African-American community.

Geech’s Bar-B-Q Pig Meat, 802 22nd Street S.

John “Geech” Black started his legendary barbecue stand in 1938 and operated it through parts of six decades at several locations along 22nd Street. Later night revelers, out-of-town guests, and students alike made a special effort to grab a pig-meat sandwich, spiced with his trademark yellow BBQ sauce.

Lost Businesses

- Kilgore’s Drugs

- Jay’s Pharmacy

- Eddie’s Shoe Shine and Repair

- Lawrence Clark Confections

- Citizen’s Lunch

- Harlem Café

- Moton’s Restaurant

- B&B Luncheonette

- Newkirk’s Steak House

- Eugene Rose’s and Dr. Orion’s Ayer’s offices

- Dixieland Beer Parlor

- Flower Brothers and Jones Furniture store

- Joe Yates, Buddy West, and William Harrington’s Barber Shops

- Jewell Ford’s Beauty Shop

- Ernest Fillyau Photography

- Central Life Insurance Company

The Interstate

Because black residents were required to stay in their own neighborhoods, they created their own businesses to serve their needs. By 1946, 58 businesses operated on 22nd Street, which grew to 100 by 1960. An estimated 75 percent were African-American owned. With the 1978-80 construction of the interstate, the community was cut in half, and the northern section disintegrated.

22nd Street S. Marker 3: Manhattan Casino Hall

Role in the Community

Originally known as the Jordan Dance Hall, this building was constructed about 1925 by Elder Jordan Sr., one of the first African-American businessmen, and his sons. The ticket window was located on the first floor. The dance hall interior was accessed by wooden steps that opened onto a large wooden dance floor in the state. A raised band stand was located at the south end, and long benches lined the walls along both sides. The building, a stop on the renowned Chitlin’ Circuit, was the focal point of culture and entertainment in the community for more than 40 years and was instrumental in the development of blues, gospel, jazz, and big band music in the South during the era of segregation. More than just a concert venue, the building played host to a variety of community events including dances, coronations, and the Gibbs High School Junior and Senior proms. At times, the Gibbs High School basketball team even held practices in the building.

Entertainment

George Grogan

George Grogan was instrumental in molding the character of the Manhattan Casino. As a concert promoter, he booked bands all over the state of Florida. Grogan is also credited with giving James Brown his start. Brown played every Thursday and Saturday night until getting his big break. In addition to promoting music, Grogan managed Jordan Park.

Goldie Thompson

Goldie Thompson, a resident of Jordan park and an ordained minister in the Baptist church, is considered a pioneer in African-American broadcasting. Thompson began promoting gospel music on the Suncoast in 1940. Initially originating his daily programs from his home, Thompson eventually landed a weekly gospel program on WHBO. By 1955, his popularity had grown, and he signed with the new all-black radio station WIOK. After WWII, Thompson took over management of the Manhattan Casino.

George Cooper band

One of the three major house bands, this 16-piece local band played for the Thursday afternoon and Friday night dances from 1936 until the 1950’s. Admission was 50-75 cents. Steve and Buster Cooper, cousins of the bandleader, went on to play with Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington.

William L. “Buddy” West

A promoter and entrepreneur, Buddy West is credited with booking the Don Redman Band, the first noted big band to perform at the Manhattan Casino. West was also responsible for booking Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller and Earl “Fatha” Hines at the Casino.

Al Downing

Al Downing is legendary to those who remember the golden days of jazz in St. Petersburg. Piano talent and a desire to perpetuate jazz among young people everywhere were two qualities Downing possessed. Downing served with the Tuskegee Airmen before leading the 613th Army Air Force Band in Tuskegee. Upon retirement, he returned to St. Petersburg where he taught at Gibbs High School and St. Petersburg Junior College.

National Musicians

Over the years, many nationally known musicians and vocalists performed at the Manhattan Casino. These included, but are not limited to, such greats as: Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughn, Fats Domino, Ink Spots, Mahalia Jackson, The Silas, Green Minstrel Show, Little Richard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Erskine Hawkins, Otis Redding, Clyde McPhatter, Brook Benton, Dizzy Gillespie, and Arthur Prysock.

22nd Street S. Marker 4: At the Crossroads

Washington’s Beer Garden and Harden’s Grocery

Businessman George Washington came to St. Petersburg about 1912 and established his own bakery and grocery. In 1939, he constructed a new two-unit building at 901-03 Street S. One side housed his beer garden. In the other side, Sidney harden opened a grocery in 1942 which became a cornerstone in the neighborhood. Offering ethnic and cultural foods, he sold Georgia sausage, hog jowls, hog’s head cheese, chitterlings, Dixie Lily grits and meal, and raw peanuts as well as foods now considered exotic: Possums, raccoons, and gopher turtles. Harden was well known for giving credit to people down on their luck. In exchange for shelling pecans or black-eyed peas or cleaning the store, he provided them with food plus a few quarters. Harden never attended school and could not read or write. However, he knew how to count money, read the scales, and remembered prices of products in the store.

Henderson’s Sundries and Barco’s Grocery

Opened around 1950, Henderson’s booths, jukeboxes, Cokes, and milkshakes created a classic mid-twentieth century teen hangout at 900 22nd Street S. Young people exchanged the latest school gossip, and the place was packed when Gibbs homecoming parades rolled through the neighborhood. A nickel in the Rockola Jukbox, which the youngsters called a “pick-a-low,” brought forth the mellow sounds of groups like the Orioles, harmonizing “Is It Too Soon to Know?” Just down the street, Paul “P.J.” Barco built the commercial building at 922-24 22nd Street S. in 1945 to house his grocery on the first floor and raise his family in the living space above. Born in 1916, he was a life-long resident of the 22nd Street neighborhood.

Barber Shop Deluxe

As 22nd Street flourished in the 1950’s, another wave of construction brought new business. In 1959, Clarence Moure built a store at909-13 22nd Street S. into which he moved his Barber Shop Deluxe. There were many barber and beauty shops in the neighborhood. These businesses served as gathering places for the community.

Funeral Homes

Like preachers and doctors, undertakers were leaders in the community to whom neighbors turned to for strength in trying times. In addition to the last rites and burials, funeral homes provided ambulance services to the injured until the 1960’s. Around 1926, Fred and Nathanial Williams opened the Williams Funeral Home at 850 22nd Street S. After the brothers died, Nathanial’s widow, Florence, managed the business with Robert Creal, who had been appointed funeral director in 1950. Six years later, the business was renamed the Creal-Williams Funeral Home, and in 1957 relocated. With it’s relocation, R.C. and Jessie Calhoun, with the assistance of experienced morticians Arthur Jerome Brown and Andrew L. Davis, established the Arch of Royal Funeral Home which moved into the building. After Calhoun’s nephew, Irving Sanchez, received his degree in mortuary science, the business was renamed the Sanchez-Arch Royal Funeral Home around 1966. Another local funeral home, Clarke Mortuary, located at 2165 7th Avenue S., opened in 1950 and was co-owned by Ernest Clarke and Elihu Brayboy, Sr.

Popular Businesses

-Sylver’s Shoe Service

-Clark Hotel

-South Side Cab Company

-Atomic Shoe Repair

-Underselling Department Store

-Clarence William’s Harlem Pool Room

-“Hoosie’s” Cozy Inn Shoe Shine Parlor

-Edna’s Flower Box

-Jordan Park Sundries

22nd Street S. Marker 5: Building 22nd Street

African-American Contractors

During the 1920’s, the demand for construction workers was so great the contractors sent agents to Georgia and Alabama to entice African-American workers to come to St. Petersburg. When a white city worker hired a black contractor to build a house for him in 1925, it was viewed by some residents as an “attempt of negroes to invade white districts.” In response, the City Commission voted that the “letting of contracts to negro contractors in the white sections of the city be disapproved,” effectively limiting African-American contractors to work in their own neighborhoods.

African-American contractors James Buggs and Thompson Kelley Childs built the buildings at 951-63, 941-47, 927-29, and 855-63 22nd Street South in 1925. Although the extent of their work may never be known, it apparent that they contributed significantly to the community. Arriving from Georgia in 1923, contractor Peter “P.P.” Perkins also built a number of significant buildings including Trinity Presbyterian Church, Melrose Clubhouse, the “gymnatorium” at Gibbs High School and the Moure Building on 909-13 22nd Street South.

951-63 22nd Street South

John Merriwether constructed this building the 1925 with 5 stores and a hotel above, one of only 5 in the city for African-Americans. Businesses located in the buildings over the years include Minnie Evans Blue Moon Beer Garden, Coleman Davis’s billiard hall, S&S Grocery, Maggie’s Beauty Box, and the Royal Hotel.

941-47 22nd Street South

Merriwether also built this three-unit building in 1925. Businesses that occupied this building include Issac Kaufman’s Dry Goods, Lester’s Dry Cleaners, Alberta Smith’s Beauty Shop, and Red Star Market. It was demolished in 1985.

931-37 22nd Street South

Sam Jones had the first 3-unit store in 1925. Businesses that occupied the building included Oscar Kleckley’s Barber Shop, Elijah Pope’s Cleaners, Vinette Sherman’s Beauty Shop, Leola’s Beauty Salon and Arthur Robinson’s Grocery. The building was demolished in 1985.

927-29 22nd Street South

Wayman Whitaker had this structure built in 1925. It had two stores and eight rooms on the second floor. Shag Restaurant, Powell’s Fish Market, and Rosa Johnson’s Restaurant occupied this building.

Commercial Vernacular Architecture

For the historic main streets across America, the storefront is the most important architectural feature. It plays a crucial role in a store’s advertising, drawing customers and increasing business. The buildings along 22nd Street S. were no exception. The buildings along 22nd are typical of 20th century commercial construction with designs indicative of the African-American main street. They are mostly two stories with large storefront windows opening to stores, restaurants, or bars on the first floor and living space above. Often, buildings were designed to accommodate several businesses.

22nd Street S. Marker 6: Royal Theater

At the time of its opening, admission prices were 40 cents for adults and 14 cents for children. In lieu of admission, children could also get in by bringing enough bottle caps from RC cola or Whistle grape, orange, or strawberry soda. The magic number of caps was reportedly 7. As an important part of the community, the Royal Theater employed many residents of the neighborhood. Often these employees performed multiple duties. For example, Melvin Smith (picture below) served as usher, ticket taker, and security along with Mack Fuller and Richard Lawson. The Royal closed in 1966, about the time integration began in St. Petersburg’s previously all white theaters to African-Americans. It has been designated a local historical landmark.

The Quonset Hut

The theater’s Quonset-hut design was a popular method of construction after World War II because the buildings were light, portable and relatively cheap to build. The name is derived from the city were the buildings were produced: Quonset, Rhode Island. Another example of the Quonset design is in the Soft Water Laundry located on the Southwest corner of 22nd St. S. and 5th Ave. S., a business, in its day, employed many residents of the community.

Showtime

The Royal theater was one of two theaters that African Americans could attend. The other, Harlem, was in the Gas Plant Neighborhood. The cry of bugles and the thunder of drums marked the theaters opening day. At the time of its opening, the Royal boasted 700 seats. Its inaugural celebration included a parade featuring a marching corps directed by scout leader, Charles “King” Tutson. A newspaper article praised it as “an inspiration for the whole community,” and it remained a major destination for 18 years. The royal also earned a reputation as being a leading venue for weekly talent shows. An article on Dec. 15, 1950 edition of the Evening Independent suggests the popularity of the talent extravaganzas during which many people performed such as 3-year old Anita Brown, who performed ballet for a huge applause and a quartet composed of Carl Brown, Jerome Brown, William Dorn and Horace Cooper sang “At Night.” Other performers mentioned included were Johnnie B. Hawkins, Caroline Payne, Bobby Burns and Frankie Mae Bivens.

22nd Street S. Marker 7: Faces and Stories

Emma Hill (ca. 1907-1924)

Bootlegging and gambling were a part of the daily life during the 1920s and 1930s. Although illegal, everyone from noted businessmen and grandmas were known to have participated. On occasion, houses were raided and moonshine was seized. One regrettable incident involved the death of 17-year-old Emma Hill when deputies fired upon a car in which she was a passenger. According to the Evening Independent, a coroner’s jury was unable to determine who killed her.

Elijah Moore (ca. 1888-1972)

Perhaps better known as the “I got ‘em” man, Elijah Moore sold peanuts and produce from a cart wearing a top hat and tails for more than 50 years. As well as being a familiar face on 22nd Street S., he was also a fixture in the annual Festival of States parades.

Henry “Rag Man” Bonner (ca. 1892-1973)

Henry “Rag Man” Bonner scoured Jordan Park and the surrounding areas in search of old rags to purchase. The rags were sold to the St. Petersburg Times for use in the production of newspaper as recycled rags were the best source of papermaking fiber. “Rag Man” Bonner strolled and drove through the streets singing in a melodious voice, “Rag man, rag, man.” When people heard him coming they would meet him on the street bringing their rags for him to buy. Bonner also sold fruits and vegetables to the people in the area, and, starting in the late 1940s, operated a junk shop at 1100 22nd Street S.

Norman Jones, Sr. (1901-1990)

Photographer, publicist, and journalist Norman Jones Sr. maintained an office at 800 22nd Street S. An astute observer of politics and culture, Jones edited the “Negro pages” in the local newspapers and wrote the column “Let’s Talk Politics” for black newspapers in Florida. Starting in 1956, Jones served as the Florida editor for the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the largest black newspapers in the U.S.

Joseph Albury (1877-1971)

A native of the Bahamas, Joseph Albury arrived in St. Petersburg in 1916. He opened a photography studio on 9th Street S. with Albert Roberts. After moving to the 22nd Street S. neighborhood in the late 1930s, he practiced photography in the neighborhood before eventually working at Gibbs Vocational School.

Betty Williams Fuller (1926-2010)

Born in St. Petersburg in 1926, Better Fuller was always described as “a pistol.” During the day, she worked at Webb’s City running the elevator where her voice was easily recognizable as she called out, “Going Up!” However, when the work day was done, Fuller could often be found at the Manhattan Casino, the place to be to dance and have fun. She was well known for dancing with the movers and shakers of the era and was said to have often asked of her many dance partners: “What’s your pleasure?”

Jewish Presence

Jewish residents were also a target of discrimination. In 1924, racist signs stating “Gentiles Only Wanted – No Jews Wanted Here” were placed along Gandy Boulevard. Although less legally imposing than the Jim Crow system, social restrictions barred Jews from membership in private clubs, residency in the fashionable neighborhoods, and eating at or staying in local restaurants and hotels which advertised “Christians Only.” As a result, Jewish entrepreneurs were largely limited to African-American neighborhoods. For example, with the construction of Jordan Park Housing Complex, Simon (Samuel) and Mollie Schwartz opened S&S Grocery in 1939. After his death in 1948, Meyer Miller, a long time Jewish employee, became the proprietor of S&S Market. The grocery provided work to children to deliver groceries to local residents, who could order their groceries and put it to a tab to pay later. The market remained a neighborhood landmark until it closed in 1969. Other Jewish entrepreneurs who operated businesses along 22nd Street S. included Morris Feltman, David Schleifer, Benjamin Bernstein, Morris Goldstein, and Samuel Rabinovitch.

22nd Street S. Marker 8: A Community of Caring

During the segregation era, many hospitals did not treat black people, either because of Jim Crow laws or the prejudiced attitude of the hospital’s administrators. Replacing a smaller hospital which had been in operation in the Gas Plant neighborhood as early as 1913, the opening of Mercy Hospital in 1923 formalized the 22nd Street S. community’s tradition of caring for its own. Built by Edgar Weeks for $68,950, the facility had 16-20 beds. Despite a dedicated group of doctors and nurses, the facility was understaffed and poorly equipped.

Initially, additions to the hospital were constructed in 1942, 1948, and 1963. Finally, on April 13, 1966, the St. Petersburg Times reported, “Mercy Hospital, 1344 22nd Street S., for many years of the municipal hospital for Negro patients, is dead. It was 43. The cause of death was listed as an overdose of red ink. The patients and staff of Mercy have been transferred to Mound Park Hospital. Only eight patients were involved in the final transfer last Friday.”

The Doctors of Mercy

In 1926, Dr. James Maxie Ponder was appointed city physician to the black community, thus becoming Mercy Hospital’s first African-American doctor. He served as the only staff physician at Mercy Hospital for more than a decade. Dr. Ponder also became the first active black member of the Pinellas County Medical Society. When he died in 1958, the flag at City Hall was lowered to half-staff, an unusual honor for a person of color in St. Petersburg. Other doctors who later worked at Mercy Hospital include Drs. Breaux Martin, Orion T. Ayer, Fred Alsup, Ralph Wimbish, Eugene C. Rose, and Harry F. Taliaferro.

The RN Club

The Registered Nurses Club, now the RN LPN Association, is the oldest black nurses organization in St. Petersburg. It was founded in 1946 by Marie Yopp. Other founding members were Catherine James, Emma Yvonne Taylor, Hannah Singleton, Effra Mae Clark, Deloris Gordon, Mattie C. Bennett, and Sadie Henry. The primary objectives of the organization were to foster better relationships between nurses and to encourage students to enter the nursing profession. They also wanted to elevate the status of nursing in the community and courage professionalism. All members were required to become members of the Disctrict 13 Florida Nurses’ Association, creating an interracial unit in 1946.

A Tradition of Midwives and Nurses

Both before and after Mercy Hospital was built, midwives were among the first to bring care to the community. The Florida School of Traditional Midwifery has said the Dept. of Health noted 4000 midwives practicing in Florida in 1920. Although it is unclear how many practiced in St. Petersburg at that time, the Pinellas County Health Dept. lists the following midwives in 1953: “Phyllis Bradwell (retired), Sally Givens (retired, Lider Gass (deceased), Carrie Zanders, Roxanna Simpkins, and Mamie Brown (retired 9/1953).”

The 1923 Mercy Hospital Annual Report stated that two African American nurses staffed the facility. Nursing staff was slowly increased. Eventually, a devoted corps of nurses performed in every aspect of care at Mercy Hospital, although they received wages far lower than their counterparts at white hospitals.

The Negro Health Clinic

The Negro Clinic, which was located adjacent to Mercy Hospital in a converted house, opened in 1940. Marie Yopp was the first registered black nurse at the clinic. In 1964, she was named supervisor of the Negro Health Clinic. She supervised black and white nurses until 1968 when the clinic was integrated with the main office of the Pinellas County Health Dept. During an early year in its existence, the clinic reported 23,724 visits from members of the community. Up until the time the clinic opened, African Americans were allowed one day a week at a white clinic downtown.

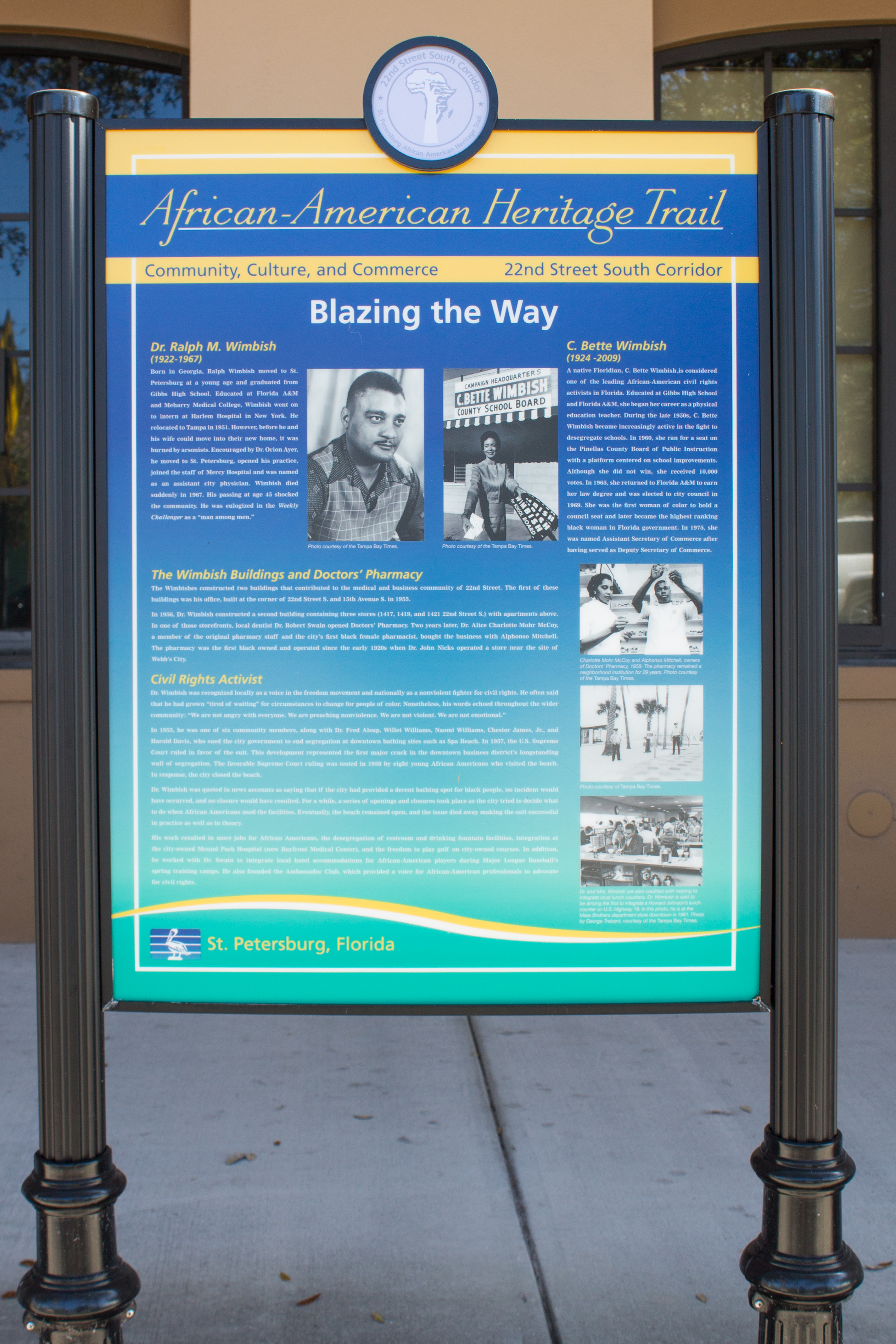

22nd Street S. Marker 9: Blazing the Way

Dr. Ralph M. Wimbish (1922-1967)

Born in Georgia, Ralph Wimbish moved to St. Petersburg at a young age and graduated from Gibbs High School. Educated at Florida A&M and Meharry Medical College, Wimbish went on to intern at the Harlem Hospital in New York. He relocated to Tampa in 1951. However, before he and his wife could move into their new home, it was burned by arsonists. Encouraged by Dr. Orion Ayer, he moved to St. Petersburg, opened his practice, joined the staff of Mercy Hospital and was named as an assistant city physician. Wimbish died suddenly in 1967. His passing at age 45 shocked the community. He was eulogized in the Weekly Challenger as a “man among men.

C. Bette Wimbish (1924-2009)

A native Floridian, C. Bette Wimbish is considered one of the leading African-American civil rights activists in Florida. Educated at Gibbs High School and Florida A&M, she began her career as a physical education teacher. During the late 1950s, C. Bette Wimbish became increasingly active in the fight to desegregate schools. In 1960, she ran for a seat on the Pinellas County Board of Public Instruction with a platform centered on school improvements. Although she did not win, she received 10,000 votes. In 1965, she returned to Florida A&M to earn her law degree and was elected to city council in the 1969. She was the first woman of color to hold a council seat and later became the highest ranking black woman in Florida government. In 1975, she was named Assistant Secretary of Commerce after having served as Deputy Secretary of Commerce.

The Wimbish Building and Doctors’ Pharmacy

The Wimbishes constructed two buildings that contributed to the medical and business community of 22nd Street. The first of these buildings was his office, built at the corner of 22nd Street S. and 15th Avenue S. in 1955.

In 1956, Dr. Wimbish constructed a second building containing three stores (1417, 1419, and 1421 22nd Street S.) with apartments above. In one of those storefronts, local dentist Dr. Robert Swain opened Doctors’ Pharmacy. Two years later, Dr. Alice Charlotte Mohr McCoy, a member of the original pharmacy staff and the city’s first black female pharmacist, bought the business with Alphonso Mitchell. The pharmacy was the first black owned and operated since the early 1920s when Dr. John Nicks operated a store near the site of Webb’s City.

Civil Rights Activist

Dr. Wimbish was recognized locally as a voice in the freedom movement and nationally as a nonviolent fighter for civil rights. He often said that he had grown “tired of waiting” for circumstances to change for people of color. Nonetheless, his words echoed throughout the wider community: “We are no angry with everyone. We are preaching nonviolence. We are not violent. We are not emotional.”

In 1955, he was one of the six community members, along with Dr. Fred Alsup, Willet Williams, Naomi Williams, Chester James, Jr., and Harold Davis, who sued the city government to end segregation at downtown bathing sites such as Spa Beach. In 1957, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the suit. This development represented the first major crack in the downtown business district’s longstanding wall of segregation. The favorable Supreme Court ruling was tested in 1958 by eight young African Americans who visited the beach. In response, the city closed the beach.

Dr. Wimbish was quoted in news accounts as saying that if the city had provided a decent bath spot for black people, no incident would have occurred, and no closure would have resulted. For a while, a series of openings and closures took place as the city tried to decide what to do when African Americans used the facilities. Eventually, the beach remained open, and the issue died away making the suit successful in the practice as well as in theory.

His work resulted in more jobs for African Americans, the desegregation of restroom and drinking fountain facilities, integration at the city-owned Mound Park Hospital (now Bayfront Medical Center), and the freedom to play golf on city-owned courses. In addition, he worked with Dr. Swain to integrate local hotel accommodations for African American players during Major League Baseball’s spring training camps. He also founded the Ambassador Club, which provided a voice for African-American professionals to advocate for civil rights.

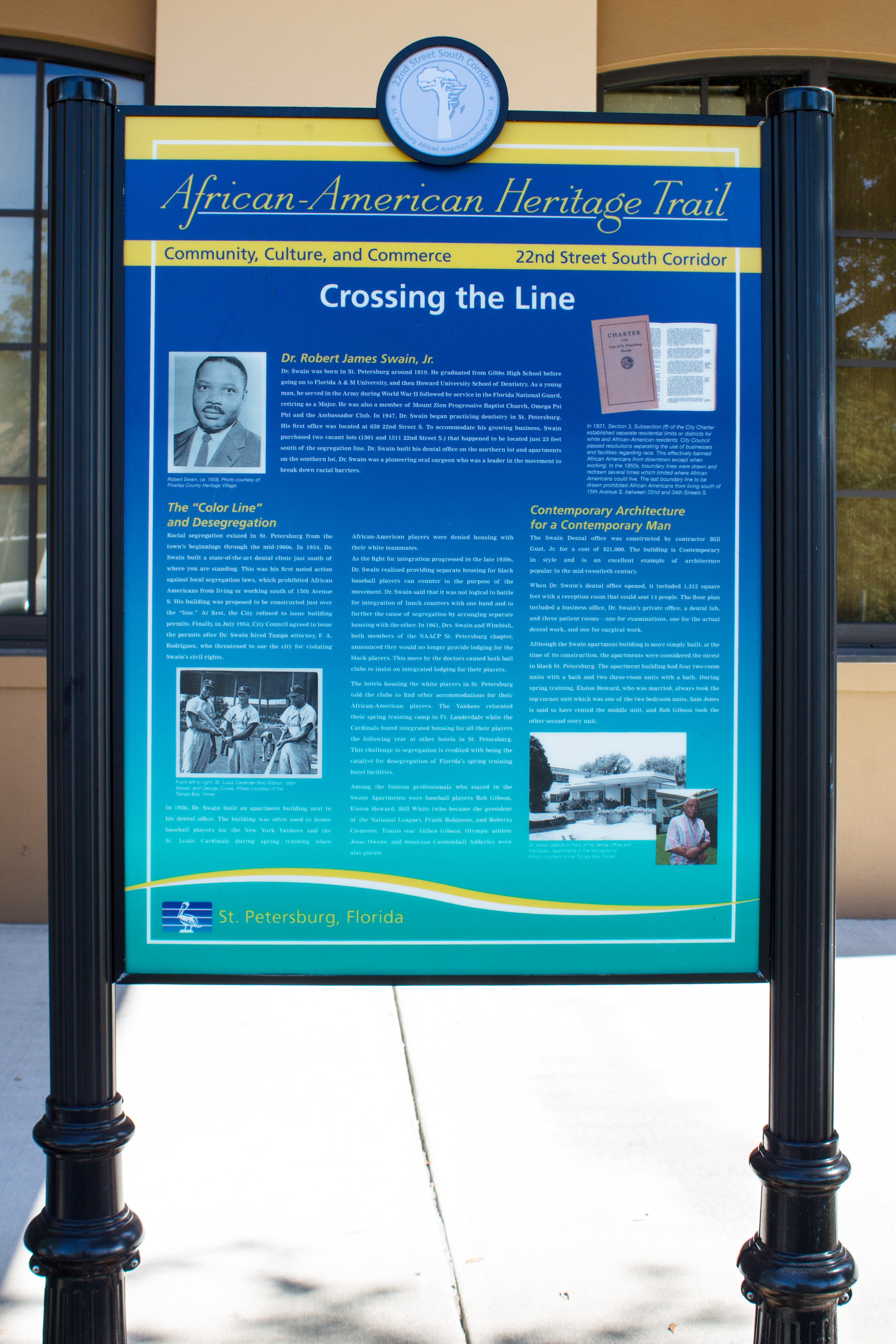

22nd Sreet S. Marker 10: Crossing the Line

Dr. Robert James Swain, Jr.

Dr. Swain was born in St. Petersburg around 1919. He graduated from Gibbs High School before going on to Florida A & M University, and then Howard University School of Dentistry. As a young man, he served in the Army during WWII followed by service in the Florida National Guard, retiring as a Major. He was also a member of Mount Zion Progressive Baptist Church, Omega Psi Phi and the Ambassador Club. In 1947, Dr. Swain began practicing dentistry in St. Petersburg. His first office was located at 659 22nd Street S. To accommodate his growing business, Swain purchased two vacant lots (1501 and 1511 22nd Street S.) that happened to be located just 25 feet south of the segregation line. Dr. Swain built his dental office on the northern lot and apartments on the southern lot. Dr. Swain was a pioneering oral surgeon who was a leader in the movement to break down racial barriers.

The “Color Line” and Desegregation

Racial segregation existed in St. Petersburg from the town’s beginnings through the mid 1960s. In 1954, Dr. Swain built a state of the art dental clinic just south of where you are standing. This was his first noted action against local segregation laws, which prohibited African Americans from living or working south of 15th Avenue S. His building was proposed to be constructed just over the “line.” At first, the City refused to issue building permits. Finally, in July 1954, City Council agreed to issue the permits after Dr. Swain hired Tampa attorney, F. A. Rodriguez, who threatened to sue the city for violating Swain’s civil rights.

In 1956, Dr. Swain built an apartment building next to his dental office. The building was often used to house baseball players for the New York Yankees and the St. Louis Cardinals during spring training when African American players were denied housing with their white teammates. As the fight for integration progressed in the late 1950s, Dr. Swain realized providing separate housing for black baseball players ran counter to the purpose of the movement. Dr. Swain said that it was not logical to battle for integration of lunch counters with one hand and to further the cause of segregation by arranging separate housing with the other. In 1961, Drs. Swain and Wimbish, both members of the NAACP St. Petersburg chapter, announced they would no longer provide lodging for the black players. The move by the doctors caused both ball clubs to insist of integrated lodging for their players.

The hotels housing the white players in St. Petersburg told the clubs to find other accommodations for the African American players. The Yankees relocated their spring training camp to Ft. Lauderdale while the Cardinals found integrated housing for all their players the following year at other hotels in St. Petersburg. This challenge to segregation is credited with being the catalyst for desegregation of Florida’s spring training hotel facilities.

Among the famous professionals who stayed in the Swain Apartments were baseball players Bob Gibson, Elston Howard, Bill White (who became the president of the National League), Frank Robinson, and Roberto Clemente, Tennis star Althea Gibson, Olympic athlete Jesse Owens, and musician Cannonball Adderley were also guests.

Contemporary Architecture for a Contemporary Man

The Swain Dental office was constructed by contractor Bill Gust, Jr. for a cost of $21,000. The building is Contemporary in style and is an excellent example of architecture popular in the mid-twentieth century. When Dr. Swain’s dental office opened, it included 1,512 square feet with the reception room that could seat 14 people. The floor plan included a business office, Dr. Swain’s private office, a dental lab, and three patient rooms – one for examinations, one for the actual dental work, and one for the surgical work.

Although the Swain apartment building is more simply built, at the time of its construction, the apartments were considered the nicest in black St. Petersburg. The apartment building had four two-room units with a bath and two three-room units with a bath. During spring training, Elston Howard, who was married, always took the top corner unit which was one of the two bedroom units. Sam Jones is said to have rented the middle unit and Bob Gibson took the other second story unit.

Copyright 2016 nicdark.com